Amy's Question

by

"Amy!"

Mrs. Grove called from the door that opened towards the garden. But no answer came. The sun had set half an hour before, and his parting rays were faintly tinging with gold and purple, few clouds that lay just alone the edge of the western sky. In the east, the full moon was rising in all her beauty, making pale the stars that were sparking in the firmament.

"Where is Amy?" she asked. "Has any one seen her come in?"

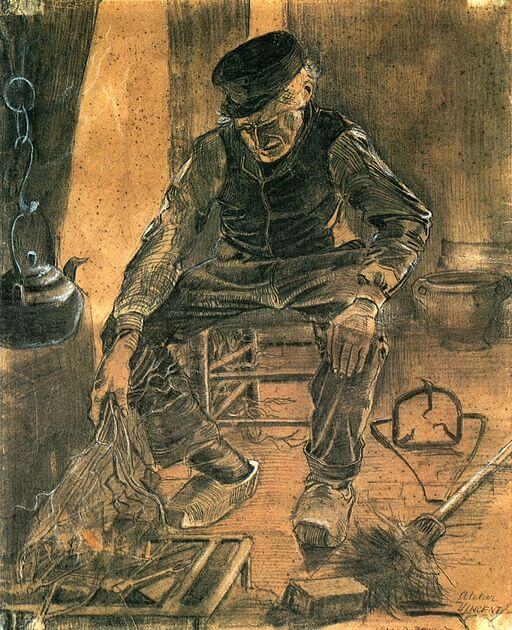

"I saw her go up stairs with her knitting in her hand half an hour ago," said Amy's brother, who was busily at work with his knife on a block of pine wood, trying to make a boat.

Mrs. Grove went to the foot of the stairs, and called again. But there was no reply.

"I wonder where the child can be," she said to herself, a slight feeling of anxiety crossing her mind. So she went up stairs to looks for her. The door of Amy's bedroom was shut, but on pushing it open Mrs. Grove saw her little girl sitting at the open window, so lost in the beauty of the moonlit sky and her own thoughts that she did not hear the noise of her mother's entrance.

"Amy," said Mrs. Grove.

The child started, and then said quickly,--

"O, mother! Come and see! Isn't it lovely?"

"What are you looking at, dear?" asked Mrs. Grove, as she sat down by her side, and drew an arm around her.

"At the moon, and stars, and the lake away off by the hill. See what a great road of light lies across the water! Isn't it beautiful, mother? And it makes me feel so quiet and happy. I wonder why it is?"

"Shall I tell you the reason?"

"O, yes, mother, dear! What is the reason?"

"God made everything that is good and beautiful."

"O, yes, I know that!"

"Good and beautiful for the sake of man; because man is the highest thing of creation and nearest to God. All things below him were created for his good; that is, God made them for him to use in sustaining the life of his body or the life of his soul."

"I don't see what use I can make of the moon and stars," said Amy.

"And yet," answered her mother, "you said only a minute ago that the beauty of this moon-light evening made you feel so quiet and happy."

"O, yes! That is so; and you were going to tell me why it was."

"First," said the mother, "let me, remind you that the moon and stars give us light by night, and that, if you happened to be away at a neighbor's after the sun went down, they would be of great use in showing you the path home-ward."

"I didn't think of that when I spoke of not seeing what use I could make, of the moon and stars," Amy replied.

Her mother went on,--

"God made everything that is good and beautiful for the stake of man, as I have just told you; and each of these good and beautiful things of creation comes to us with a double blessing,--one for our bodies and the other for our souls. The moon and stars not only give light this evening to make dark ways plain, but their calm presence fills our souls with peace. And they do so, because all things of nature being the work of God, have in them a likeness of something in himself not seen by our eyes, but felt in our souls. Do you understand anything of what I mean, Amy?"

"Just a little, only," answered the child. "Do you mean, mother dear, that God is inside of the moon and stars, and everything else that he has made?"

"Not exactly what I mean; but that he has so made them, that each created thin is as a mirror in which our souls may see something of his love and his wisdom reflected. In the water we see an image of his truth, that, if learned, will satisfy our thirsty minds and cleanse us from impurity. In the sun we see an image of his love, that gives light, and warmth, and all beauty and health to our souls."

"And what in the moon?" asked Amy.

"The moon is cold and calm, not warm and brilliant like the sun, which tells us of God's love. Like truths learned, but not made warm and bright by love, it shows us the way in times of darkness. But you are too young to understand much about this. Only keep in your memory that every good and beautiful thing you see, being made by God, reflects something of his nature and quality to your soul and that this is why the lovely, the grand, the beautiful, the pure, and sweet things of nature fill your heart with peace or delight when you gaze at them."

For a little while after this they sat looking out of the window, both feeling very peaceful in the presence of God and his works. Then voice was heard below, and Amy, starting up, exclaimed,--

"O, there is father!" and taking her mother's hand, went down to meet him.

by

"Amy!"

Mrs. Grove called from the door that opened towards the garden. But no answer came. The sun had set half an hour before, and his parting rays were faintly tinging with gold and purple, few clouds that lay just alone the edge of the western sky. In the east, the full moon was rising in all her beauty, making pale the stars that were sparking in the firmament.

"Where is Amy?" she asked. "Has any one seen her come in?"

"I saw her go up stairs with her knitting in her hand half an hour ago," said Amy's brother, who was busily at work with his knife on a block of pine wood, trying to make a boat.

Mrs. Grove went to the foot of the stairs, and called again. But there was no reply.

"I wonder where the child can be," she said to herself, a slight feeling of anxiety crossing her mind. So she went up stairs to looks for her. The door of Amy's bedroom was shut, but on pushing it open Mrs. Grove saw her little girl sitting at the open window, so lost in the beauty of the moonlit sky and her own thoughts that she did not hear the noise of her mother's entrance.

"Amy," said Mrs. Grove.

The child started, and then said quickly,--

"O, mother! Come and see! Isn't it lovely?"

"What are you looking at, dear?" asked Mrs. Grove, as she sat down by her side, and drew an arm around her.

"At the moon, and stars, and the lake away off by the hill. See what a great road of light lies across the water! Isn't it beautiful, mother? And it makes me feel so quiet and happy. I wonder why it is?"

"Shall I tell you the reason?"

"O, yes, mother, dear! What is the reason?"

"God made everything that is good and beautiful."

"O, yes, I know that!"

"Good and beautiful for the sake of man; because man is the highest thing of creation and nearest to God. All things below him were created for his good; that is, God made them for him to use in sustaining the life of his body or the life of his soul."

"I don't see what use I can make of the moon and stars," said Amy.

"And yet," answered her mother, "you said only a minute ago that the beauty of this moon-light evening made you feel so quiet and happy."

"O, yes! That is so; and you were going to tell me why it was."

"First," said the mother, "let me, remind you that the moon and stars give us light by night, and that, if you happened to be away at a neighbor's after the sun went down, they would be of great use in showing you the path home-ward."

"I didn't think of that when I spoke of not seeing what use I could make, of the moon and stars," Amy replied.

Her mother went on,--

"God made everything that is good and beautiful for the stake of man, as I have just told you; and each of these good and beautiful things of creation comes to us with a double blessing,--one for our bodies and the other for our souls. The moon and stars not only give light this evening to make dark ways plain, but their calm presence fills our souls with peace. And they do so, because all things of nature being the work of God, have in them a likeness of something in himself not seen by our eyes, but felt in our souls. Do you understand anything of what I mean, Amy?"

"Just a little, only," answered the child. "Do you mean, mother dear, that God is inside of the moon and stars, and everything else that he has made?"

"Not exactly what I mean; but that he has so made them, that each created thin is as a mirror in which our souls may see something of his love and his wisdom reflected. In the water we see an image of his truth, that, if learned, will satisfy our thirsty minds and cleanse us from impurity. In the sun we see an image of his love, that gives light, and warmth, and all beauty and health to our souls."

"And what in the moon?" asked Amy.

"The moon is cold and calm, not warm and brilliant like the sun, which tells us of God's love. Like truths learned, but not made warm and bright by love, it shows us the way in times of darkness. But you are too young to understand much about this. Only keep in your memory that every good and beautiful thing you see, being made by God, reflects something of his nature and quality to your soul and that this is why the lovely, the grand, the beautiful, the pure, and sweet things of nature fill your heart with peace or delight when you gaze at them."

For a little while after this they sat looking out of the window, both feeling very peaceful in the presence of God and his works. Then voice was heard below, and Amy, starting up, exclaimed,--

"O, there is father!" and taking her mother's hand, went down to meet him.